When you are injured in an accident, insurance companies often focus on one question: Are your injuries actually connected to what happened? That connection is what lawyers and courts call proximate cause.

A proximate cause is the legal way of asking whether someone’s actions (or failure to act) are closely enough tied to your harm to hold them responsible. In California personal injury cases, causation is often framed using the “substantial factor” concept, which we explain below in everyday terms.

If an adjuster is saying your injury is “unrelated,” you are not alone. Causation disputes come up all the time in car accidents and other injury claims, especially when symptoms show up later, there was a prior condition, or more than one event may have played a role.

Quick Answers / Key Takeaways

- Proximate cause is the legal link between an event and an injury.

- California often uses a “substantial factor” standard when discussing causation.

- An injury can have more than one cause and still be connected to an incident.

- Insurance disputes often focus on delayed symptoms, prior conditions, or gaps in treatment.

- A clean timeline + documents + medical records usually help support causation.

- Be careful with early insurance conversations because wording can be taken out of context.

- If you want help sorting out causation questions, Law Offices of Brent W. Caldwell offers free consultations and handles personal injury cases on a contingency fee basis.

Proximate Cause: The Legal Link Between Negligence and Injury

Proximate cause is one of the core building blocks in many personal injury claims because it answers a practical question: Did the incident actually lead to the harm being claimed? Even when someone did something careless, a claim can still be disputed if the other side argues the injury is too far removed from the event.

A helpful way to think about it is this:

- Negligence is about conduct (what someone did or failed to do).

- Causation is about connection (whether that conduct led to the injury).

- Damages are the losses (medical bills, missed work, pain, and other impacts).

Proximate cause lives in the “connection” part. It is not about proving that an accident happened. It is about showing that the accident and the injury belong in the same story, not two separate stories.

People often get tripped up because causation has two layers that can sound similar.

Actual cause vs proximate cause (why both get discussed)

You may hear two phrases: actual cause and proximate cause.

- Actual cause often gets described as: “Would this injury have happened if the event never occurred?”

- Proximate cause asks a different question: “Is the injury closely enough tied to the event to hold someone responsible under the law?”

That second question is where disputes tend to show up. Insurance companies may accept that a crash occurred, yet still argue that a specific diagnosis, body part, or course of treatment is “not related.”

If you are dealing with that kind of pushback, a simple first step is to build a clean, dated timeline (symptoms → care → work impact) and keep your supporting documents together.

Foreseeability (why the law draws a line)

Foreseeability is a concept that often comes up when deciding whether a chain of events is too stretched out.

The law generally looks for a link that makes sense in real life, not a connection that depends on a long series of unlikely events. That does not mean the exact injury needs to be predicted in advance. It means the harm should not be so unusual or remote that holding someone responsible would feel disconnected from what happened.

This is also why “proximate cause” can become a major issue in cases involving:

- Multiple events (a crash, then a later incident)

- Delayed symptoms (pain that shows up days later)

- Prior conditions (old injuries or degeneration that show up on imaging)

- Complications (medical issues that arise during treatment)

California’s “Substantial Factor” Standard (CACI 430)

When people search “proximate cause law” in California, they are often looking for the practical rule courts use. In many California civil cases, juries are instructed on causation using a concept called “substantial factor.” You will sometimes see this tied to California’s civil jury instructions, commonly referenced as CACI 430.

A substantial factor is more than a remote or trivial factor. It does not have to be the only cause of harm. It just needs to meaningfully contribute to it.

That framing matters because it matches how real accidents work. Injuries often have more than one influence—prior health history, a hard impact, a delayed flare-up, a course of treatment—yet the question is whether the incident was still a meaningful part of why the harm occurred.

More than remote or trivial

“Remote or trivial” can sound abstract, so here is a practical way to think about it:

- Remote/trivial: A link that feels stretched, speculative, or only slightly connected.

- Substantial factor: A link that fits the facts and the timeline in a real-world way.

This is why documentation becomes so important. When the timeline is clear—what happened, what you felt, when you sought care, what the records say—it is easier to show the connection is not a guess.

If insurance is focusing on one small detail (a delay in treatment, a prior ache, a single note in a chart), that is often a sign they are trying to characterize your injury as “remote” from the incident.

Multiple causes (CACI 431) and why it is common

California instructions also recognize that more than one cause can contribute to an injury. That matters in situations like:

- A multi-vehicle collision where more than one driver’s actions played a role

- An accident that aggravates a prior condition

- A situation where pain builds over time, then becomes clear days later

- Treatment complications or overlapping medical issues

The big point is not “one perfect cause.” It is whether the incident was a meaningful cause under the substantial factor concept.

We will get more practical in the next section by walking through the most common ways causation gets challenged in personal injury claims, and what tends to make those disputes harder or easier to sort out.

The Most Common Proximate Cause Disputes in Injury Claims

If you feel like insurance is questioning whether you are really hurt, what they are often doing is challenging causation, the connection between the incident and the injury. This is one of the most common pressure points in personal injury claims because it can affect what the insurer is willing to pay, what treatment they consider “related,” and how they frame your credibility.

Below are the patterns we most often see when proximate cause is disputed. Reading these does not mean your claim is “bad.” It usually means you need a clearer record and a cleaner timeline.

Pre-existing conditions and degenerative findings

Many people have imaging results that show “degeneration,” “arthritis,” or older changes even if they were not having serious symptoms before an accident. Adjusters may use those words to argue:

- “This was already there.”

- “The accident did not cause it.”

- “Your pain is just natural wear and tear.”

What often gets lost is that causation questions are not always all-or-nothing. In real life, an incident may trigger symptoms or make an existing condition worse. The details matter: what you could do before, what changed after, and what your medical records say about onset and progression.

Gaps in treatment or delayed symptoms

Delays happen for everyday reasons: you were focused on your car, work, family obligations, or you assumed the pain would go away. Insurers still often point to gaps and say:

- “If it was serious, you would have gone right away.”

- “The delay shows the accident did not cause it.”

- “Something else must have happened.”

Some injuries can feel mild at first and become clearer later. That said, gaps make disputes easier for the insurer because they can argue the connection is uncertain. What helps is straightforward documentation: when symptoms began, how they changed, and why care occurred when it did (without guessing or exaggerating).

Intervening events that can break the chain

An intervening event is something that happens after the incident that the insurer claims is the “real cause.” Common examples include:

- A later fall or new accident

- A strenuous activity that flared symptoms

- A return to work that worsened pain

- A significant time gap with no documented complaints

Not every later event “breaks the chain,” but these situations often get more complicated because the insurer will try to separate your injuries into neat boxes. This is where the “substantial factor” idea we covered above becomes important: the question is often whether the original incident still meaningfully contributed to the harm, even if other things occurred later.

Comparative fault vs causation

People often mix these up.

- Comparative fault is about who shares responsibility for the incident.

- Causation is about whether the incident caused the injury being claimed.

You can have a causation dispute even when fault seems clear (like a rear-end crash). You can also have shared fault and still have injuries that are connected to the incident. These are separate issues, and insurers sometimes blur them in conversation.

If you are hearing “unrelated,” “pre-existing,” “no objective findings,” or “delay in care,” you are likely in a causation dispute.

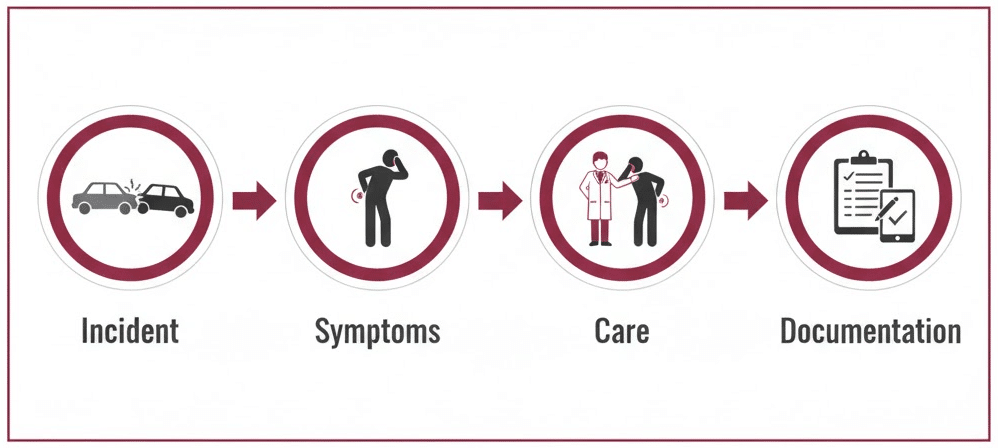

The Causation Proof Map: Timeline, Records, Photos, Witnesses

When causation is disputed, the most helpful thing you can do (without getting pulled into legal arguments) is to organize your facts in a way that makes the connection easy to follow. Think of this as a “proof map”: a simple set of categories that often matter when an insurer is deciding whether an injury is related to an incident.

Build a clean timeline

A timeline is often the fastest way to cut through confusion. Keep it simple and dated.

Include:

- Date/time of incident

- Symptoms you noticed first (even if mild)

- When symptoms changed (worsened, spread, new limitation)

- Medical visits and key recommendations

- Time missed from work or activities you could not do

- Any later events that may come up (even if you think they are unrelated)

Tip: A short timeline that is consistent with your medical records tends to carry more weight than a long story that is hard to verify.

Gather incident documents and media

These items can help confirm what happened and how severe it was:

- Crash/incident report (if one exists)

- Photos and video (vehicles, scene, visible injuries, hazards)

- Witness names and contact info

- Tow/repair records (in auto cases, these can help show impact severity)

- Exchange of information (insurance, driver details)

If you do not have everything, that is common. Start with what you have and keep it in one folder.

Medical records and consistency

Medical records are often where causation disputes are won or lost because they document:

- When you reported symptoms

- What you said caused them

- Objective findings (when available)

- Treatment course and response

- Work restrictions or functional limits

One reason adjusters focus on gaps and prior conditions is that they are looking for inconsistencies. If you notice something in a record that seems off (wrong date, wrong mechanism, missing symptom), it is usually better to address it calmly and promptly than to ignore it.

When experts can come up

In some claims, especially those involving complex medical questions, a prior condition, multiple incidents, or a big disagreement about mechanics, experts may become part of the discussion. That can include medical professionals or other qualified evaluators who help explain how an injury can relate to an event.

You do not need to “solve” this on your own. The practical goal is to keep your timeline and documentation organized so the right questions can be answered with real records instead of assumptions.

If an insurance company is calling your injury “unrelated,” it often helps to talk with a California-licensed personal injury lawyer who can look at the facts in context. Law Offices of Brent W. Caldwell offers free consultations, and we handle personal injury cases on a contingency fee basis.

Realistic Hypotheticals: Where the Chain Holds and Breaks

Sometimes proximate cause feels confusing because real life is messy. These hypotheticals show how California’s “substantial factor” framing often gets discussed in everyday terms. They are examples only, not legal advice, and real cases depend on specific facts.

Rear-end crash

Scenario: A driver is stopped at a red light in Huntington Beach and gets rear-ended. They feel “tight” the same day, then neck and back pain ramps up over the next week. They see urgent care a few days later, start physical therapy, and miss work shifts.

Where the chain often holds: The timeline is straightforward: impact → symptoms → treatment → work impact. Even if the pain worsens over several days, the records can still show a consistent progression.

Where it can get challenged: If there is a long gap in care, or the first medical note says “no pain” and later notes say the opposite, insurers may argue the link is uncertain.

Multi-vehicle chain reaction

Scenario: On the 405, one car stops suddenly, several cars collide, and multiple drivers may share responsibility. A person in the middle car ends up with shoulder and wrist injuries, but the insurer argues “you were already hit once before the final impact,” or “another driver caused most of it.”

Where the chain often holds: Multiple causes do not automatically defeat causation. The question is often whether the collisions were meaningful contributing factors to the injuries, even if responsibility is shared.

Where it can get challenged: When there are several impacts, insurers may try to slice the event into separate “mini-accidents” and argue the injury belongs to one moment, not the others. Clear photos, damage records, and a clean symptom timeline can help keep the story coherent.

Premises liability scenario

Scenario: A shopper slips on a wet floor at a store, falls, and later develops knee pain that worsens over time. Imaging shows degenerative changes, and the store’s insurer argues the knee issue is “pre-existing” and not from the fall.

Where the chain often holds: If the person was functioning normally before, then pain and limitations began after the fall and are documented in medical notes, the fall may still be a meaningful contributing factor.

Where it can get challenged: If the first medical record does not mention the fall, or there were prior knee complaints that are not addressed clearly, insurers may argue the symptoms are unrelated.

Mistakes That Can Weaken Causation (Even When You Are Hurt)

When an insurer disputes proximate cause, they are often looking for reasons to say the injury story “does not add up.” Many of the problems they point to are avoidable. Others happen innocently because people are trying to get back to normal.

These are common mistakes we see that can make causation harder to show, even when someone is genuinely hurt.

Delayed documentation

Pain and limitations can change quickly after an incident. If nothing is written down early, it becomes easier for an insurer to argue that symptoms started later for some other reason.

Helpful habits:

- Write a short note the same day or next day: what hurts, where, and what you cannot do

- Update it if symptoms change (worse, new area, headaches, numbness, etc.)

- Save basic items that show impact on life: missed work messages, modified duties, canceled plans

You do not need a long diary. A few dated lines can be enough to keep your timeline clear.

Recorded statements

Adjusters may ask for a recorded statement early, sometimes before you have a full medical picture. People can unintentionally downplay symptoms or guess about medical issues they do not understand.

Common pitfalls:

- Saying “I am fine” because you are trying to be polite

- Guessing about what is wrong medically

- Agreeing with leading questions that minimize the incident

If you are unsure what to say, it is reasonable to slow the process down and get clarity first. If you are feeling pressured by insurance, we can talk through safe basics during a free consultation.

Social media

Posts are often taken out of context. Even normal activities can be framed as proof that you are not injured.

Examples that can create headaches:

- Photos at a family event with no explanation of pain or limitations

- Comments like “Feeling better” that do not match what records show

- Location tags that suggest activity levels the insurer will interpret aggressively

If you post, be mindful that it may be read with skepticism.

Skipped follow-up care

Not everyone can be treated consistently. Costs, work schedules, transportation, and family demands can interfere. Insurers often still argue that missed appointments mean the injury was not serious or was not related.

If you miss care:

- Keep your timeline accurate about why (work conflict, symptoms changed, could not get in, etc.)

- Communicate with your provider as appropriate so the chart reflects what happened

- Avoid disappearing for long stretches without any record if symptoms are ongoing

The overall theme is consistency: consistent timeline, consistent reporting, and consistent documentation.

Next Steps When an Adjuster Says Your Injury Is “Unrelated”

Hearing “your injury is not related” can feel like the insurer is calling you dishonest. In many cases, it is simply a strategy to narrow what they will accept and pay for. The goal is to respond with organized facts, not frustration.

Document and organize

Start by pulling your claim into one place so the story is easy to follow:

- Your timeline (incident → symptoms → care → work/life impact)

- Photos/video of the scene, vehicles, visible injuries, hazards

- Incident report (if available)

- Witness contact information

- Basic out-of-pocket expense list (prescriptions, co-pays, transportation)

If you have already gathered some of this, that is a strong start. If you are missing items, write down what you remember while it is still fresh.

Clarify medical questions

Causation disputes often turn on what the records say and how consistent they are over time. You do not need to argue medical points with an adjuster.

Practical steps that often help:

- Review your visit summaries for obvious errors (wrong date, wrong side, missing mention of the incident)

- Keep track of referrals, restrictions, and follow-up recommendations

- If your symptoms changed (worse later, new area), note the dates so your timeline stays accurate

If you notice something that does not match what happened, it can be worth addressing it calmly and promptly rather than hoping it does not matter.

Communicate carefully with insurance

When causation is disputed, adjusters may ask questions designed to get short answers that sound like admissions.

General guardrails:

- Stick to what you know (dates, symptoms, treatment), not guesses

- Avoid “always/never” statements when your symptoms fluctuate

- Be cautious with statements like “I feel fine” when you mean “I am managing today”

- If you are asked for a recorded statement and you feel uncomfortable, it is reasonable to pause and get guidance

Talk with a personal injury lawyer

If causation is becoming the main issue, a consult can help you understand:

- What the insurer is really disputing (injury, treatment, timing, or something else)

- What documentation may matter most in your situation

- How California’s “substantial factor” concept may apply to your fact pattern

The Law Offices of Brent W. Caldwell is based in Huntington Beach and our lawyers are licensed to practice in California. We offer free consultations, and we handle personal injury cases on a contingency fee basis.

Proximate Cause FAQs (California Personal Injury Claims)

What is proximate cause in personal injury law?

Proximate cause is the legal way of describing the connection between an incident and an injury. It asks whether the incident is closely enough tied to the harm to hold someone responsible under the law.

What is the difference between actual cause and proximate cause?

Actual cause is often framed as “would this have happened without the incident,” while proximate cause focuses on whether the injury is sufficiently connected and not too remote. Both can come up when causation is disputed.

What does “substantial factor” mean in California?

In many California civil cases, causation is discussed using a “substantial factor” concept, meaning the conduct contributed to the harm in a meaningful way and was more than a remote or trivial factor. How that applies depends on the facts and evidence.

Can there be more than one proximate cause?

Yes. Injuries can have multiple contributing causes. A claim does not automatically fail just because more than one factor may be involved.

Does proximate cause require foreseeability?

Foreseeability is often part of how proximate cause is analyzed, especially when the chain of events is long or unusual. The idea is to draw a reasonable line so liability does not extend to highly remote outcomes.

What breaks the chain of causation?

A later, separate event can sometimes be argued to interrupt the link between the original incident and the injury. Whether it does depends on what happened, the timeline, and the medical record.

If I had a pre-existing condition, does that end my claim?

Not necessarily. Causation disputes often involve whether an incident contributed to symptoms or made a condition worse. That is typically evidence-driven and depends on documentation.

What if my symptoms showed up days later?

Delayed symptoms can happen. Insurers may question the connection, so keeping a clear timeline and consistent medical history often matters.

Why does the insurance company say my injury is “unrelated”?

Causation disputes are common in injury claims. Insurers may point to gaps in care, prior conditions, or alternate explanations to limit what they accept as related.

Do I have to give a recorded statement to the other driver’s insurer?

Many people feel pressured to do so quickly. It is reasonable to be cautious and understand what is being requested before speaking, especially if you are still learning the full extent of your injuries.

What evidence helps show proximate cause after a car accident?

A clean timeline, incident documentation (photos, report, witnesses), and medical records that consistently connect symptoms to the event often help support causation.

Who decides proximate cause in a California case?

It depends on the posture of the case, but causation is often addressed through evidence and, when a case proceeds, jury instructions that explain the legal standard.

How long do causation disputes take to resolve?

It varies widely based on the facts, medical issues, and jurisdiction.

Can I talk to a lawyer just to understand whether causation is an issue?

Yes. If you are hearing “unrelated,” “pre-existing,” or “gap in treatment,” a consultation can help you understand what is being disputed and what documentation may matter. Law Offices of Brent W. Caldwell offers free consultations and handles personal injury cases on a contingency fee basis.